In studying the locomotion of the last common ancestor (LCA) of Homo and Pan, a scarcity of fossil evidence has forced researchers to rely on indirect methods to infer its traits. Two primary approaches are used: the paleontological approach, which attempts to reconstruct locomotion from fragmentary fossil records, and the neontological approach, which relies on comparative anatomy among extant primates such as Homo, Pan, and Gorilla. Although both approaches provide valuable insights into the possible characteristics of the LCA, their heavy reliance on inference prevents their conclusions from being definitive.

The paleontological approach focuses on narrowing down a range of potential fossil candidates and using early hominins to make informed reconstructions of ancestral traits. However, this method leaves considerable room for error. While identifying a range of fossil candidates may constrain hypotheses, it does not allow for firm conclusions. Similarly, the neontological approach faces comparable limitations. This approach assumes that traits shared between Homo and Gorilla—with Gorilla serving as the outgroup—were present in the Homo–Pan LCA. However, this assumption rests on the inference that these shared traits are homologous. While some similarities may indeed reflect traits inherited from a common ancestor, others may instead result from convergent evolution or homoplasy, which weakens their relevance to reconstructing the LCA.

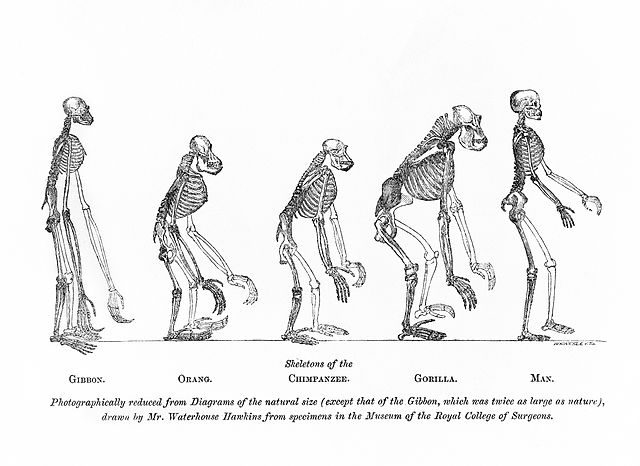

Despite the uncertainty inherent in both approaches, several hypotheses regarding Homo–Pan LCA locomotion have been proposed. One early hypothesis suggested that the LCA was an arboreal quadruped, the most common form of locomotion among primates. This theory was quickly rejected due to the relatively small body size of arboreal quadrupeds compared to early hominins, as well as the absence of a dorsally positioned scapula that would permit the increased forelimb mobility observed in hominins.

Another hypothesis proposed that Homo and Pan evolved from a terrestrial quadrupedal ancestor similar to baboons. This theory was also deemed unlikely, as terrestrial quadrupeds possess deep thoracic cavities and shoulder socket orientations that limit forelimb mobility. In contrast, hominins exhibit curved digits, suggesting adaptation to a more arboreal environment rather than the terrestrial habitats occupied by such quadrupeds.

A more compelling hypothesis draws comparisons between the Homo–Pan LCA and hylobatids, small-bodied arboreal bipeds. Many traits observed in hylobatids, such as gibbons and siamangs, are also present in early hominins, including curved digits, long arms, shallow thoraxes, and highly mobile shoulder joints. These similarities suggest a potential evolutionary relationship. However, this hypothesis raises important concerns. While these traits support arboreal competence, they are also strongly associated with brachiation. To date, there is limited evidence to suggest that brachiation, rather than more generalized vertical climbing or clambering, played a dominant role in early hominin locomotion. Additionally, the significant body size difference between hylobatids and early hominins makes it unlikely that hominins evolved directly from a hylobatid-like ancestor.

The locomotion of the LCA may be best explained by a large-bodied vertical climber and suspensor that also engaged in knuckle-walking. Such an ancestor would possess mobile forelimbs and hindlimbs as well as an orthograde posture—traits observed in early hominins. Research has shown that vertical climbing in chimpanzees activates muscle patterns more similar to those used in human bipedalism than those used during quadrupedal walking, suggesting that vertical climbing may have served as a precursor to bipedal locomotion. Although early models of the LCA excluded knuckle-walking, later studies identified anatomical features shared between knuckle-walkers and hominins. Richmond and colleagues proposed that transverse wrist stabilization and an extended wrist posture in humans may be retained traits from knuckle-walking ancestors. This proposal suggests a functional link between knuckle-walking and hominin evolution, though its validity remains debated. Additional similarities, such as heel-strike mechanics observed in both humans and African apes, further support the potential role of knuckle-walking in shaping hominin locomotion.

Despite substantial support for the vertical climber and knuckle-walker hypothesis, recent studies have renewed arguments in favor of a more generalized quadrupedal LCA. Research by Tim White, Owen Lovejoy, Gen Suwa, and colleagues on Ardipithecus has suggested affinities with arboreal quadrupeds. Evidence for this claim comes primarily from reconstructions of the Ardipithecus hand skeleton, which lacks the wrist rigidity characteristic of knuckle-walkers. Additionally, the metacarpals of Ardipithecus are relatively short, providing limited support for suspensory behaviors. However, these conclusions remain contentious. Critics note the absence of comparisons with Miocene apes such as Oreopithecus, which exhibits hand morphology associated with suspensory locomotion. Furthermore, the estimated body mass of Ardipithecus (~50 kg) raises questions about its ability to navigate arboreal environments effectively. As with earlier hypotheses, interpretations of Ardipithecus are constrained by incomplete fossil evidence. For example, muscle attachment sites on the humerus have been central to discussions of LCA locomotion, yet such features remain poorly preserved and difficult to interpret.

In summary, numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain the locomotion of the last common ancestor of Homo and Pan, each supported and challenged by varying lines of evidence. Among these, the vertical climber and knuckle-walker model remains the most strongly supported, though it is not without limitations. Competing hypotheses suffer from similar shortcomings, primarily the lack of a complete fossil record. Ultimately, a more definitive understanding of the Homo–Pan LCA will require new fossil discoveries. Until then, the neontological and paleontological approaches remain the most effective tools available for reconstructing this critical stage of primate evolution.

– Written by Johnathan Chapp