Written by Akhil Kondepudi

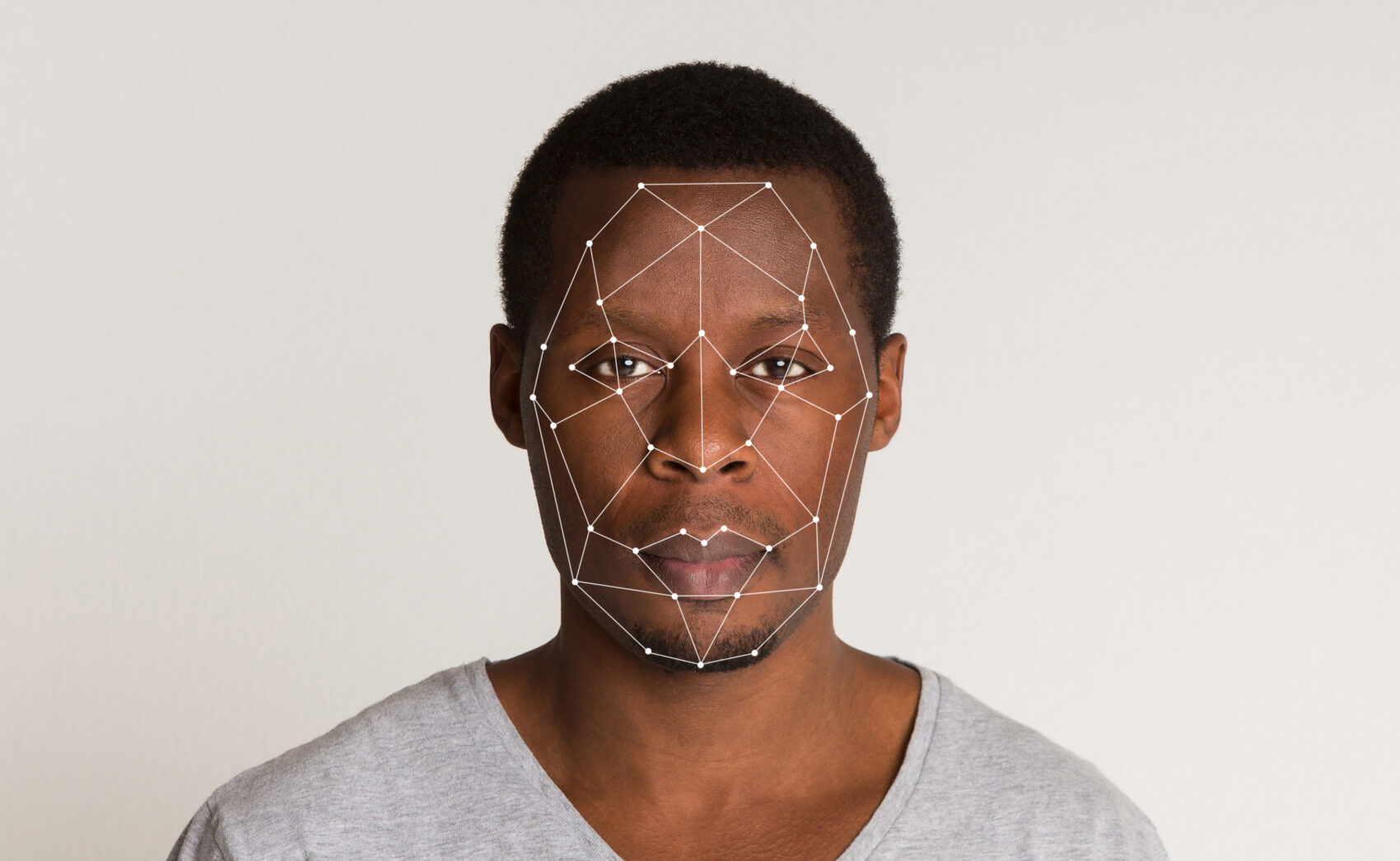

The mention of AI may bring self-driving cars, Siri, or the Terminator to mind. Widely used nowadays to describe any “intelligent” system, artificial intelligence (AI) is a subset of data science that uses complex statistical models to learn data features. In other terms, it teaches itself to understand the characteristics of data provided, allowing it to predict outcomes and provide new insights. One of the many ways it has changed our world is healthcare, which incorporates state-of-the-art models to improve patients’ experiences and prognoses. For example, AI can aid doctors in classifying diabetic retinopathy. However, AI models can reflect bias in their training datasets: a critical ethical issue, especially in healthcare, where a wrong decision could be the difference between life and death. Recent work has exposed how racial bias is often prevalent in these AI models and leads to racial disparities in applications in AI. In this piece, I will explain how the development of healthcare AI places racial minorities at risk and the steps we can take to protect them and ensure this revolution takes place for the benefit of all.

A significant example of racial bias in medical AI that garnered much media attention was the classification of skin cancers. Many research groups had trained AI models on millions of skin cancer images to achieve the highest accuracy. However, testing these models in hospitals revealed a troublesome issue: they performed poorly in the black population! People wondered, how is this possible after rigorous testing? After subsequent studies, the answer became clear: the training data contained very few samples from black people. Racial minorities were significantly underrepresented because the researchers had assumed skin cancer affected everyone the same way. However, race does play an essential role in cancer diagnosis, making it foolish not to include it in the AI model. Now, imagine if this AI had assisted in a more immediate life-and-death situation and its subsequent effects on racial minorities. Researchers cited the lack of training samples as the problem: they used data from premier hospital institutions, which had a skewed patient distribution in terms of race. Additionally, the patient’s consent is required to use their data, and racial minorities may be more skeptical of this technology. However, as we saw, their skepticism may lead to medical AI being harmful to them. Thus, we must first understand the challenges underlying representation before finding solutions to ensure no harm.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted many examples of bias in medical AI. In a recent study in Nature, researchers found that programs designed to help individuals with complex medical needs, including COVID-19, were less likely to select black people than white people. The underlying issue was like the problem with skin cancer classification: the people designing the algorithms had made incorrect assumptions. They believed that the average black and white person in their dataset had similar health-related costs. However, the black population, on average, utilizes less healthcare coverage and care than the white population for the same medical problems, making it appear that they require less consideration, such as problems designed to help those with complex health needs. Since the algorithm was designed to target those who were potentially at a high risk based on cost, it showed bias when it came to the race of the individual in question. This example demonstrates that the problem does not lie in the actual AI but the people designing it. Their assumptions can misinform the AI, leading to erroneous and potentially deadly outcomes, and, worse yet, this problem exists everywhere. A study in Science discovered racial bias in an industry-standard AI algorithm that identifies whether patients with complex medical needs require aid. This bias arises from the fact that racial minorities, on average, lack access to medical resources, resulting from systemic racism.

Not only does a racial disparity exist in the training of AI, but one also exists in its application. Properly trained AI models exist in medicine, with little to no bias regarding race. However, these advancements are not available for the entire population. Hospitals in underserved areas may lag in innovation and not implement these models to better their patients. Recently, there has been an effort to bring the benefits of medical AI to those disproportionately affected. For example, AI-based applications exist to summarize complex health information so that anyone can understand it, making it useful for those who do not have readily available access to a primary care provider and may have questions regarding their health.

With the immense prevalence of AI in healthcare, we need to address the problem of racial bias in algorithms used every day. We must start at the level of the government. Recently, the Biden administration announced a national AI initiative, led by leaders in AI around the country. This office needs to work with organizations like the National Institutes of Health and Health and Human Services Department to study how exactly AI is being used to address the nation’s health and whether it harms citizens. Solutions include a systemic overview of hospitals’ algorithms used to rank patients by need via testing over a racially balanced dataset and subsequent efforts to better algorithms.

Additionally, we should create a balanced dataset by creating a consortium of hospitals to collect data from individuals of all backgrounds to ensure that medical AI is unbiased. Finally, technology giants like Google and Facebook have indirect access to medical information. For example, Facebook has developed AI to detect whether its users may be depressed or at risk of suicide. While they state they are using it to help their users, they could potentially target specific individuals with ads utilizing this data and profit commercially. Thus, I strongly advocate for regulations prohibiting these corporations from using this medical data for commercial purposes. Overall, there needs to be tight regulation of the development of medical AI, and this can only start at the policy level.

Artificial intelligence has been instrumental for healthcare over the past decade, enabling medical providers to better care for their patients. However, as I’ve demonstrated, it also poses a risk to only help a select population and potentially harm others, especially racial minorities. The thought of an algorithm making a mistake in a life-or-death situation is genuinely terrifying, even more so if it was the mistake of the humans designing that algorithm. Therefore, we need to ensure the development of medical AI stays on the right path and benefits everyone.

Works Cited

Chen, Mei, and Michel Decary. 2020. “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: An Essential Guide for Health Leaders.” Healthcare Management Forum / Canadian College of Health Service Executives = Forum Gestion Des Soins de Sante / College Canadien Des Directeurs de Services de Sante 33 (1): 10–18.

Eichstaedt, Johannes C., Robert J. Smith, Raina M. Merchant, Lyle H. Ungar, Patrick Crutchley, Daniel Preoţiuc-Pietro, David A. Asch, and H. Andrew Schwartz. 2018. “Facebook Language Predicts Depression in Medical Records.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (44): 11203–8.

Lashbrook, Angela. 2018. “AI-Driven Dermatology Could Leave Dark-Skinned Patients Behind.” The Atlantic, August 16, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/08/machine-learning-dermatology-skin-color/567619/.

Ledford, Heidi. 2019. “Millions of Black People Affected by Racial Bias in Health-Care Algorithms.” Nature.

Obermeyer, Ziad, Brian Powers, Christine Vogeli, and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2019. “Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used to Manage the Health of Populations.” Science 366 (6464): 447–53.

Raman, Rajiv, Debarati Dasgupta, Kim Ramasamy, Ronnie George, Viswanathan Mohan, and Daniel Ting. 2021. “Using Artificial Intelligence for Diabetic Retinopathy Screening: Policy Implications.” Indian Journal of Ophthalmology69 (11): 2993–98.

“The Biden Administration Launches the National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Task Force.” 2021. June 10, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2021/06/10/the-biden-administration-launches-the-national-artificial-intelligence-research-resource-task-force/

Wang, Jonathan Xin, Sulaiman Somani, Jonathan H. Chen, Sara Murray, and Urmimala Sarkar. 2021. “Health Equity in Artificial Intelligence and Primary Care Research: Protocol for a Scoping Review.” JMIR Research Protocols 10 (9): e27799.